Sneeze Diary

Ben Barker

7th March 2013

At Boring conference this year, Roo Reynolds spoke about collecting things. Among the curiosities one project particularly stood out, Peter Fletcher’s Sneeze Diary, ostensibly a record of every time he sneezes, but as he explains, it’s more than that. My interest centred on a couple of things.

Impartial Record

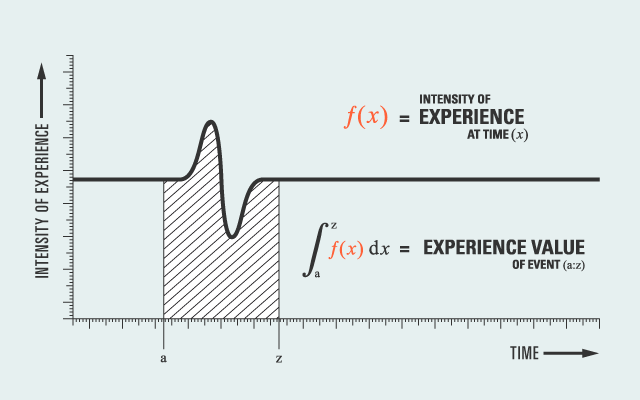

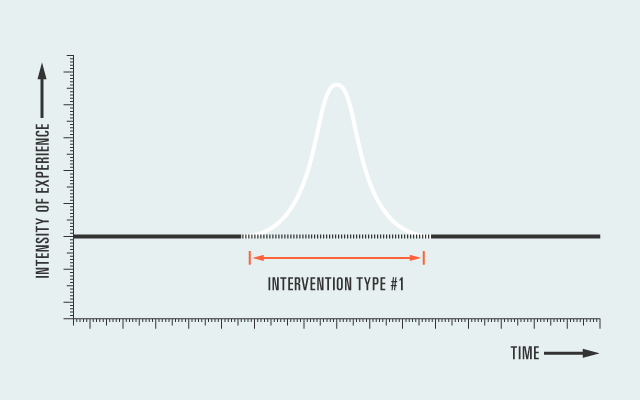

The sneeze diary creates a random, almost completely impartial record of a daily life. It scoops the mundane, the exceptional and the frustrating up into the same timeline to be reflected on side by side. I did some work on this with the watch camera a few months ago exploring non-partisan interventions that help understand the impact of all experiences, be they strong or weak, positive or negative. Typically we’re only good at capturing the strong positive experiences, it’s hard to critique such a skewed record.

The religious associations with sneezes gives them a resonance the camera doesn’t have, whilst being self-generated seems to makes it less of an imposition. As a caution, I wonder how long it takes before it begins to feel like a voluntary action, a reaction to boredom. In the same vein Peter has ways of managing his sneezes when it’s not convenient, say when he is on the toilet or away from his notebook.

Memento Mori

It’s also a momento mori. Forcing reflection by interjecting into your routine, lifting you from the moment and up into the larger narrative of your life. It asks you to remember both the moment and the journey, like stars on an ocean voyage. As Peter says:

This act of counting, and documenting, not only acts to highlight, intensify and enhance the experiences that accompany a sneeze, but also the events that fall between the sneezes, giving me a more profound understanding, even than I had before, of the simple joy in the passing of time

It’s a beautiful piece of design. Peter talks about how over time, it starts to seem unnatural when he sees someone sneeze and not make a note, and that’s the final proof. It’s a habit changing intervention, that reaches beyond the moment you sneeze and out into an exploration and reflection on what it’s like to be you. It’s an enhancing behaviour.

Once I had been counting sneezes for a short time, I became disturbed when I saw someone sneeze, and then not look closely at their watch or mobile phone and take out and write something illegible in a notebook. Witnessing people sneeze and then not record it has come to feel unsettling and wrong, as if they are losing the sneeze, letting it go to waste. Does this mean I am enhancing my life by counting my sneezes?

My own sneeze diary is an inelegant system, I just make a new evernote note for each sneeze. I have thoroughly enjoyed doing it and can’t imagine ever stopping. I love having this parallel, awkward record of my existence, that captures me next to radiators or at the kitchen sink as often as it finds me doing something memorable in the traditional sense.

As a side note, with evernote you get heaps of meta data, which is a point worth raising. Is adding extra meta data more loaded than an idea this elegant deserves? For the sake of this record I’ve added the date, but suspect it perhaps detracts. This may be the only place I don’t agreed with Peter though, the rest is poetry.

Sneeze Diary: #1-31

NOVEMBER

#1 / 25th Double. Central line, just out of Boring. Pizza for dinner?

#2 / 28th Hereford Arms, Gloucester Road. Friend through to the finals of the Game Lab.

#3 / 30th Cold morning at the studio. Working on the advent calendar.

#4 / 30th Just had a peice of chewing gum. Selling my iPhone on the forum.

DECEMBER

#5 / 3rd Double. Exactly midnight, editing Playable Cities document to send to everyone. Bit of a cold.

#6 / 3rd Part cough. Watching David Attenborough in Madagascar, laughing about dating an egg.

#7 / 18th 3 in quick succession. Making Saturday coffee, empty day stretching out before me.

#8 / 24th Double. Walking down stairs past Christmas stockings. Dry warmth and green/grey carpet of my parents house.

JANUARY

#9 / 2nd Double. At home, putting washing on the radiator. Festive hangover, no strong emotion.

#10 / 10th Part cough double, chewing gum induced. Laptop into bag, drink with friend cancelled. Free evening.

#11 / 19th Single. At home, morning before Playable City award announcement. Went to the mirror to watch myself sneeze.

#12 / 19th Delayed double. Making coffee, discussing the guy who thought the whole household was unemployed.

#13 / 22nd Big double, cathartic. Leaving work to do tax return at home.

#14 / 24th Single. Holding a full cup of tea, required some balance. Packing bag for training at Leyton Orient ground.

FEBRUARY

#15 / 2nd Nasal double, directed at carpet. Drinking an Erdinger, editing detective interview.

#16 / 5th Double, chesty. Lying on my side, 6.30am wake up for filming at BBR.

#17 / 4th Double, throaty. Night before going to India. Closing laptop, heading home.

#18 / 5th Rapid double. Packing for India, thinking about linen shirts.

#19 / 5th Single, just taken off out of Heathrow. Using the inflight seat to seat messaging service.

#20 / 11th Double, in Afgan airspace. Tired, watched The Help, nearly cried.

#21 / 11th Single, over Eastern Europe. Watching Brazil.

#22 / 11th Cough-like sneeze, single. Heathrow airspace, the City and the City.

#23 / 12th Single, muffled by a developing cold. Writing Mind film questions, thinking about new world wines.

#24 / 12th Single. Realising the event is paid.

#25 / 13th Single, Ill. Checking the map of Africa.

#26 / 25th Single, cycling. Fake Nike trainers and a sunset. 6-0 at football.

#27 / 26th Single, expecting a second. You’re so smart and I can’t wait to see you

#28 / 27th One sneeze, kicked out of pub. Drunk, Cheese.

#29 / 28th Single. Bacon sandwich and horror films.

MARCH

#30 / 3rd Single. Waiting for the 78, about to buy a kilo of sausages.

#31 / 5th Double. First sunny day in March, thinking beyond lunch.

#32 / 5th Three part single. Beer on the stoop, and a medicinal airwave

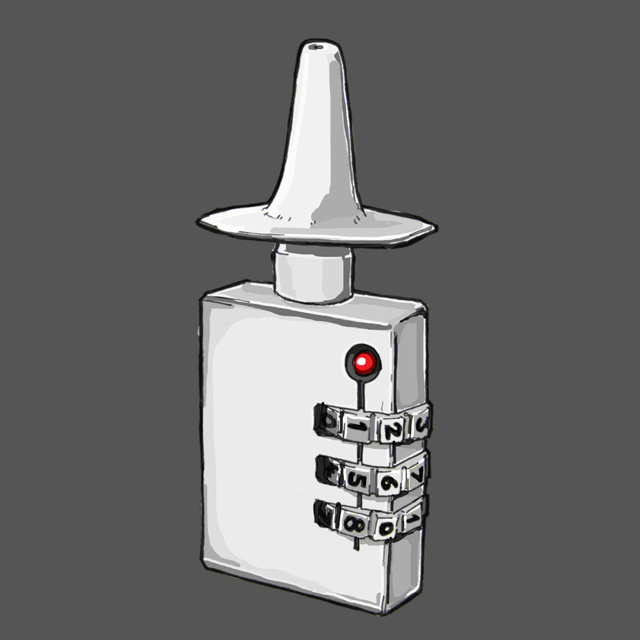

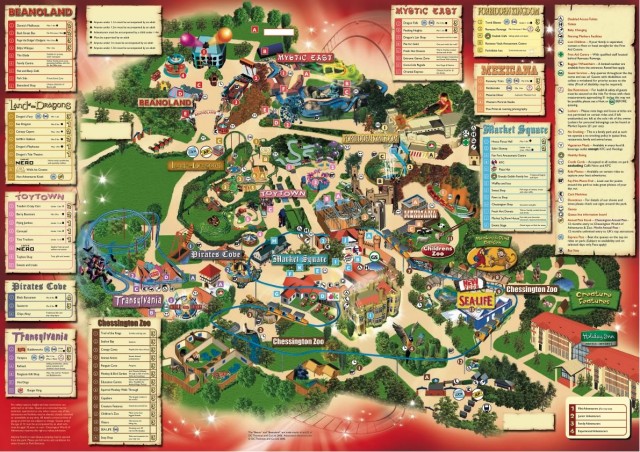

Siren Diary

We extended the idea for our recent trip to Unbox in Dehli, to make a micro version over the four days of festival. We called it the siren diary, and an alarm went off at intervals through out the four days. It was fairly unsuccessful as people were so busy, so we changed to become the sirens ourselves using a video camera. We hoped to start conversations about how people reflect and build on experiences, how we manage the passing of time and what it takes to shake up a routine. Here are some of the responses to the question, “what are you thinking about?”

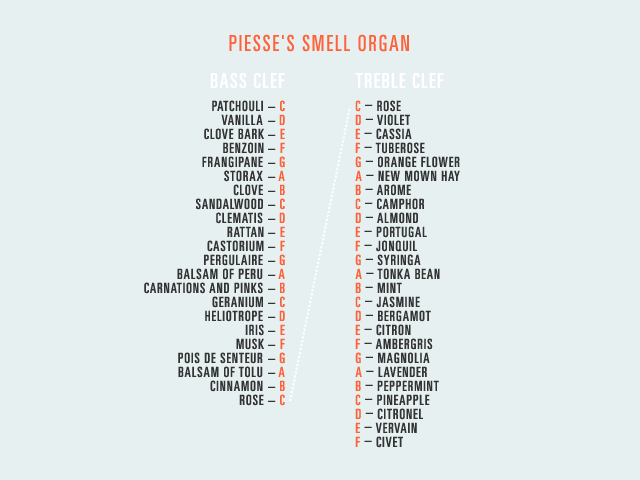

Perhaps the nicest thing we heard was a girl who for every term throughout her 4 years of college used a different perfume. She saw it as a way of separating and remembering the stages in her life. It’s another beautiful intervention, giving episodes a specific smell and acknowledging them as descrete periods, strung together to form a whole. It makes standing at the dresser applying perfume an act of understanding, a smile at times passing.