Sam Hill

2nd December 2013

How are cities in computer games different from other fictional cities?

Across film, television and literature, from Minas Tirith via Gotham to Neo Tokyo, we’ve been carefully shepherded – like tourists to North Korea – through a great number of fictional cities. This is even before taking into account the extrapolation, contortion and parody of real locations (Ghostbusters II New York, Lock Stock’s East London, Police Academy 7’s Moscow) and sci-fi future visions of the familiar (Blade Runner‘s Los Angeles, Escape From L.A.’s Los Angeles and Demolition Man’s San Angeles).

As artistic renderings, these fictions tell us something about the cities we do live in. They painstakingly depict moments in time, or guide us between heady vistas whilst showing us something about how we live with ourselves and each other.

But how much further can visual media inspire our future cities? In London at least, there’s no shortage of projects designed to make the city a greater spectacle to behold. One of London’s premiere forms of attraction has become platforms to view the city – not so much as a street-level, person-watching flâneur, but as a helicopter-jockey/shiny glass evangelist. From the Shard, the Millennium Eye, the Emirates ‘Air Line’ cable cars, to Heron Tower, Centre Point, Tate Modern’s Members room and a myriad of other rooftop terraces between Hoxton and Peckham, we’re encouraged to pay exorbitant amounts for the luxury of a high-up window.

Games developers are more obliged than other media creators to take their visions of urban life and render them in greater depth. An immersive world can’t depend too heavily on hyperbole to elicit an emotional response from us. So though the whole must still be compelling to take in, every component nook and cranny must also bleed with the same character and message – there is no space or scale for ambiguity or misdirection. When a writer tells you something is so, and a director shows you something is so, a developer – a simulator – must appear to have made it so.

Cities in games need arguably do two things: first of all they must simulate a functioning society, though granted only so far as the realism of the game demands. Secondly, critically, they must still be fun places to be in and interact with.

It is therefore appropriate when we consider how our living environments can be more experientially enriching, that we should look to simulated spaces to learn how they have done the same. What can the real learn from the simulacrum?

When the City is the Star

In the UK, post-war development and ubiquitous brand enfranchisement have created such homogeneity across urban centres that our high streets have become all but interchangeable. So it can be incredibly refreshing to visit fictional cities with such rich and distinct identities. Some games have created incredible works of art, in the form of habitable cities – atmospheric, detailed, awe-inspiring, textured, multi-faceted, believable, subtle, and vast. Mentioning said cities by name can elicit a stronger emotional response than by mentioning any of their particular denizens.

Bioshock remains a premier example of this – personally, when I hear the mention of “Rapture”, it stirs up a greater sense of wonder, dread and melancholy than any particular antagonist of the series. Similarly, memories of the broken Prague-like City 17, and her painterly Victorian cousin Dunwall, can tug at the heart strings stronger than Alyx, Emily or any other major character from their respective titles.

Grand Theft Auto has delivered a mixed bag of cities over the years (actually other than Vice City they’ve been pretty well realised), but arguably the most recent incarnation of Los Santos has been their richest and most compellingly built environment yet.

These non-places, though unreal, have the integrity to hold together many individual strands of narrative, are open to several perspectives, and can survive the same schisms as our real cities – luxury and squalor; old and new; alien and familiar.

Playground Cities

Dishonored‘s aforementioned island capital Dunwall and GTA’s Los Santos sit alongside Batman’s Arkham City district, I Am Alive‘s Haventon and any one of Assassin Creed’s historic set-pieces – but perhaps most notably 15th century Venice – as cities designed from the rooftops downwards with a single goal: to be playgrounds, specifically climbing frames, equal parts vertical and horizontal. Digital environment design for play is a challenging, experimental process in itself, but these spaces are fantastic for giving the tactile and stealthy movement of their characters the full potential.

On the surface this kind of physical exploration and play seems comparable to parkour, though in reality parkour is about exploiting and negotiating an unyielding environment. These spaces, rather than being re-appropriated by the player as it first seeems, have been painstakingly designed to work harmoniously together with the nuances and limitations of player movement to create a very gratifying play experience.

Sanctuaries in a Harsh World

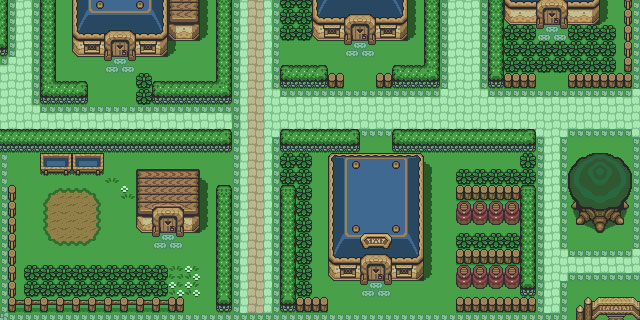

Though often little more than settlements, the villages, towns and cities that pepper the landscape of many RPG landscapes, from the homely back-water starter town to the mid-game metropolitan base of operations, often serve two roles.

The first is R&R – a safe bastion in an otherwise dangerous and untamed wilderness. A small haven of civilisation (It’s difficult not to feel sorry for the unfortunate folk who have to endure our adventure worlds permanently). This is somewhere to sleep and (sometimes literally) recharge – probably there will be a tavern in which to rest one’s head, consolidate some XP and save current progress.

It’s common for cities to have tall, impenetrable walls; the only entrance being a single,well-guarded main gate (and possibly a few sewer grates). Though this is mostly done to economise on memory (such as Megaton in Fallout 3, or the compartmentalized Imperial City in Elder Scrolls: Oblivion), the psychology of these safe zones shouldn’t be underestimated. The walls draw a definite boundary between the chaotic danger of ‘the wild’ and the enforced civility of ‘the tame’ and it’s common for city guards to patrol the streets too, should the player wish to upset this balance themselves. These proto-cities re-enact what our earliest settlements were founded for: municipal protection racketeering.

They are such palpably different environments from outside the walls, that for a player that has spent a long time dungeoneering the break in pace can be very cathartic. Completed quests are often rewarded in cities and so these digital spaces can become strongly linked with a sense of gratification and closure.

Whilst refuelling, it’s very likely that there will be a general store to buy essentials, like food and healing materials. RPG settlements are interestingly distinct from their real-world counterpoints for being engineered entirely for the benefit of the player, and this is often thinly veiled. If there are a handful of special interest/niche stores in town, it’s more than likely that they will cater specifically to the needs of the player – a place to trade encumbering loads of loot for shiny new weapons, armour or scrolls. Though economic on reality, these townships are dead on the money for providing for the needs of their market – even if it is, effectively, a market for one.

The second role of RPG settlements is to drive the main narrative forward – this is the home of the brief-dispatching wizened sage or beleaguered king. But the taverns will probably have a few troubled souls within them too – cities are great places for lightweight side-quests, testing the player’s otherwise undeveloped genteel skills – silver-tongued charisma, lock-picking or bartering. Any mercenary tasks that do take place within the city walls are distinctly less strenuous then those beyond them – rats in the basement etc – further reinforcing the message of a step down in difficulty.

Simulation Cities

Obviously, city builder and management sims (Sim City, Transport Tycoon, Anno 1701, plus some real-time strategies like Age of Empires) give us the opportunity to understand the city from a different, top-down perspective, and allow us to create or modify these spaces in a manner that we prefer. They are interesting for helping us to see first-hand the reliance we have on infrastructure, and the socio-economic factors that make up (according to somebody’s model) a well-balanced environment for living and working.

They also give us a licence to consider how our cities could be better designed – more efficient, more sustainable, or with improved lifestyle opportunities.

Minecraft deserves a mention in this camp because even though, as a sandbox game, its grit is finer than most, the vast majority of building blocks are still implicitly designed for habitation. Below is an example of perhaps the twentieth sincere attempt I’ve made at starting a township – this time a Mediterranean-style fishing village.

Cities as Part of a Larger System

Finally there are the cities that are part of a bigger scheme – such as in Risk-like military conquest games. In particular there is the Civilization series where we see a city as a desirable, possessable machine, able to convert inputs – food, raw materials, energy, luxury, trade networks, healthcare and security – into outputs: revenue, scientific advancement, industry and culture.

Who’s calling the shots

Our living cities can be more like the ones we experience in computer games – aware of their own rich identity, affording more opportunities for narrative, interaction and play – if the architecture and infrastructure were designed with these affordances in mind.

This isn’t necessarily about vertigo-inducing stunts or god-like power play, but there is still the potential for contextual, located fun and intervention points to be soft- and hard-built into the city systems. The challenge is partially about trust – a trust between denizens and governing bodies. Play is inhibited when permissions are removed and activity is restricted, for the sake of our safety and protection.

However the larger issue is lack of motivation from decision making parties. Companies and organisations are the main powers that change the form of our modern cities. There isn’t a lot of impetus between the vanity of the prestigious client and the vanity of their equally prestigious architectural firm to create any emotional engagement with their spaces, other than a reserved and passive sense of awe – which locks us back in to the look-don’t-touch world of cinematic cities. Even shopping centres and high street stores prescribe a very limited form of engagement, wrapped up in a particular model of consumption. This is a shame because with a more playful attitude, spatial designers could tap in to a much deeper vein of emotional engagement through their work, and their clients would benefit from having a more integral and meaningful link with the community around them.