A Fork in the Road

Ben Barker

2nd September 2014

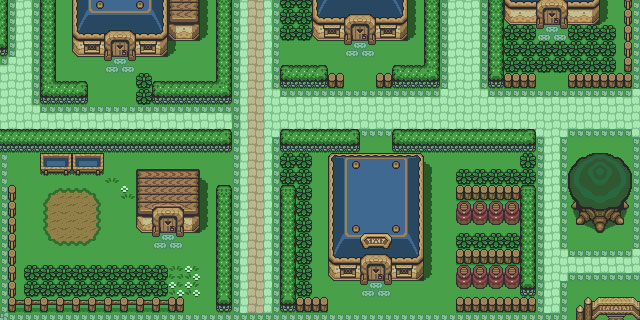

Last month we launched a small prototype of a new project called A Fork in the Road. Somewhere between a game and a storytelling platform, it works using the path and road network of the city as a framework to tell branching stories. In its current incarnation players use text messages to relay content and every junction has multiple directions, allowing players to decide how to progress. The prototype ran for four days in the American city of Indianapolis to coincide with a games festival called GenCon and we aimed to learn how both players and writers responded to the mechanic.

The Streets as Interface

The idea was partially conceived during Hello Lamp Post last year. As the experience was drawing to a close in Bristol, we hid a small branching narrative around the harbour. Only a handful of people encountered it, but the idea of city-based branching narratives kept nagging away at us. Then earlier this year we were speaking with John and Vishant at Concept Catapult in Indianapolis about GenCon and we realised that there was a perfect interface to manage those divergent choices: the city streets.

Streets make a great overarching story management grid, but are also completely legible by players at ground level. Located games have often abstracted the city to use its grid for excellent projects like Crossroad or Pacmanahatten, but we were influenced as much by the physchogeography of Iain Sinclair or Janet Cardiff’s Missing Voice which are both completely located and could only ever be experienced in one place. Interestingly neither could be played using street view, you have to enter buildings and look under benches to make the story work.

Implementation

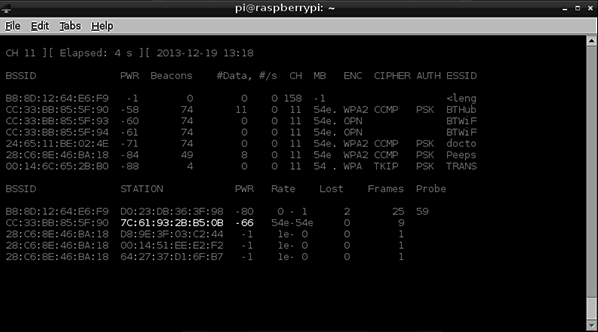

We always felt this mechanic could work using anything from a Choose Your Own Adventure style book, which anyone who was a child in the 80s or 90s know, through to a GPS powered app. The choice to use SMS for the prototype came down to its ubiquity and accessibility. SMS means a player can go from zero awareness of the game, to playing, within 30 seconds. It’s also a very intimate medium – easy to suspend disbelief and imagine the message are being written by a remote ally, who’s carefully following your every step.

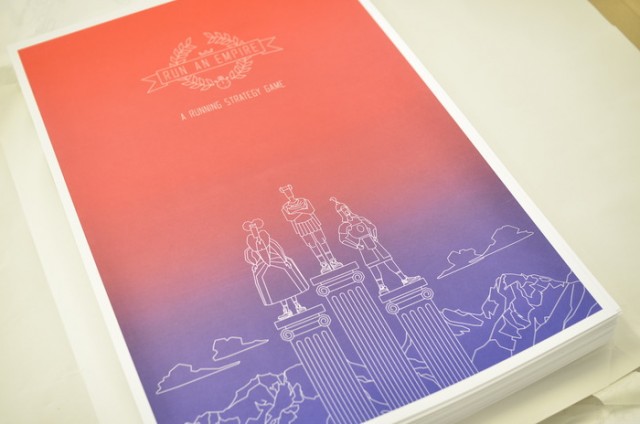

Even as we developed the idea and cemented the plan to create an SMS prototype for GenCon, we realised the potential implementation was very broad. Should the platform focus on competitive, game like experiences using chance, conditional modifiers and character progression? Players could play in groups and race to solve problems. One can imagine six friends starting out to solve a mystery, taking different journeys through the cityand arriving at a final point each with a different set of clues with which to approach the finale. Or the platform could be a collaboratively sourced narrative mechanic, where an exquisite corpse interaction combines with a peer voting system to create an evolving picture of local storytelling.

Story branches could be persistent, meaning multiple narrative threads could intersect a junction. Alternatively the junctions could be persistent, meaning the same context always exists but character state (e.g. ‘player has met npc x’) influence the interaction and possible outcomes.

With so many potential mechanics to explore we decided the first step was to build a simple prototype, get some users involved and test the premise of narrative-in-situ itself.

Writing for the City

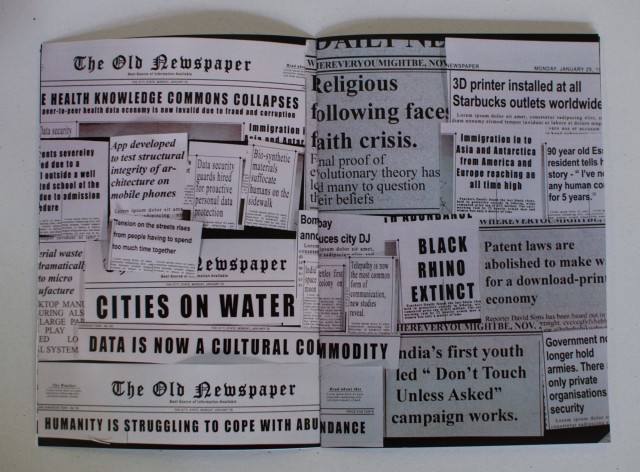

The writing style naturally felt like it should be in the spirit of Dungeons and Dragons, writers should construct story worlds for people to explore where the rules and realities were dependant on the imagination of the Dungeon Master. We spoke to a lot of writers and they mostly proposed an approach that played with fact and fiction, often building on city myths or playing with the history of place. We knew the system could work either entirely using fact as an enhanced city tour, or as fantastical tales rooted in the sights and sensations of the city, most of our authors chose abstract fiction that explored the in-between space.

Now, following on from the success of the playtest narrative, we have a story being written for Halloween by Janet Fry based on Washington Irving, an Indianapolis-based author and his story within in a story: The Sketch book of Geoffrey Crayon. We also have a tale just completed by Julie Young about the SS Indianapolis, the shark attack its crew faced and its role in the film Jaws.

However, as the initial playtest loomed, we realised we would need to write our own narrative to prove and articulate the nuances of the platform. So with a lot of help and research into local history, we pulled together a story around a historical quirk: In the 1860s a small town just outside Indianapolis called Boggstown had seceded from the Union. Simultaneously, Morgan, a Confederate general, was moving north in his infamous race through Union heart lands. In his party he had a Telegrapher, known for his skill with misinformation and propaganda. Our conceit was that there was a legacy of his work still existing in Boggstown and a shadowy operation was still exerting influence to this day. Some one called Ellsworth is connected and you’ve just received a message from him.

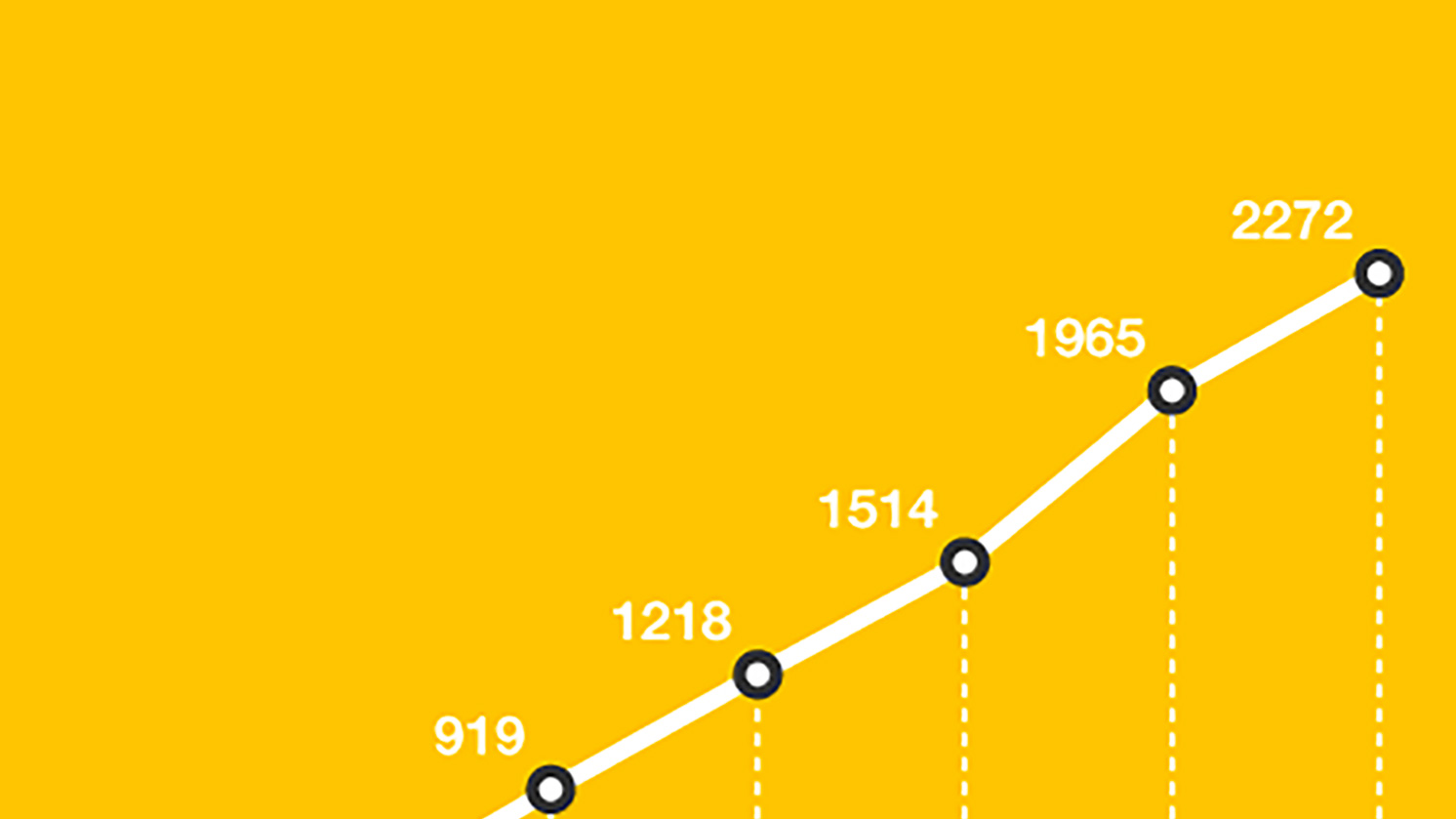

After a series of iterations and play tests the mechanic and story seemed to go down really well. Below are a couple of players in front of the war memorial in the heart of downtown Indianapolis. If you are in Indianapolis and want to play, let us know, the stories are still up and running. They all start from a specific plaque in the city. The Irvington Halloween story will start from a small local bookstore, the Civil War Boggstown narrative starts form the convention center and the SS Indianapolis starts form the Soldiers and Sailors monument.

Next Steps

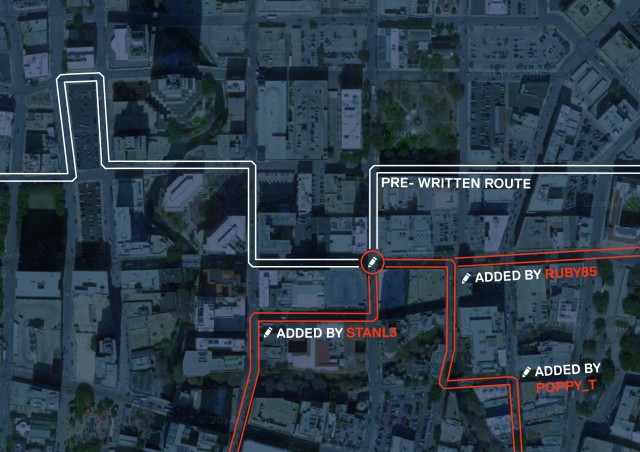

From our work in Indianapolis we quickly saw that the challenge was not so much to communicate the premise to players, as it was to explain how the mechanic worked to writers. Writing good branching narratives is hard, a point reinforced by Glynn Cannon’s piece on the subject that nagged throughout the writing process. There has been so much enthusiasm from writers to create content for the system that we need an interface that lets them prototype, visualise and mange the expanding complexity of a branching narrative. We have begun testing different map based UIs to help people write directly in location.

The other idea that has come out really strongly is a more democratic writing process. The line between player, and contributor is very thin. People want to add to and improve the stories, even more so whilst they’re out on the street, playing the game. We’ll hope to test how writers can open up stories to be forked and added to by citizens. Local people will know the best legends, locations and secrets of a place, the exquisite corpse of story telling in location has real potential.

We ran a small writing workshop at GenCon to generate new content and contexts for the application. We’d love to collaborate with other organisations to create a story that takes players to and from places of interest while telling them an engaging story. So of course, if you think your community or audience has a story to tell or you have a journey you’d like to take them on then please get in touch, we’d love to work with you.