Proposition: The Anti-Camera

Sam Hill

7th June 2012

(Photo courtesy of Russell Davies)

Cameras as Diminutive Relays

Whilst we’re waiting for Paul to ready himself for the second round of Paul’s Gamble, we’re kicking off a research project based upon a relatively nascent behaviour, practised by many folk to varying extents. It’s become a bit of a contentious bugbear in the studio, but I find myself doing it all the time. To illustrate, here’s a quote pulled right from the bleeding edge of contemporary culture, The Blair Witch Project (1999):

Doomed Teen #1: “I see why you like this video camera so much.”

Doomed Teen #2: “You do?”

Doomed Teen #1: “It’s not quite reality. It’s like a totally filtered reality. It’s like you can pretend everything’s not quite the way it is… It’s not the same on film is it? I mean, you know it’s real, but it’s like looking through the lens gives you some sort of protection from what’s on the other side.”

I don’t personally take issue with video cameras being used as creative tools, or to document and share events with others. I appreciate (and actively condone) the importance of creating or finding mementos, which cameras do very well. The relationship between value of experience and the fallibility of memory is something we believe is vitally important to explore. The real issue is in the way cameras are used during salient, important events as a diminutive relay for experience. Camera phones being as ubiquitous as they are, it’s common at any public gathering – firework display, festival, parade or sunset in a beer garden – to see a forest of arms raised above heads, awkwardly waving miniature, two-dimensional proxies of the spectacle ahead. Everyone with their arm in the air is not looking at the point of interest, but their own screen, carefully making sure they are ‘capturing’ every detail for some assumed posterity.

The problem is, we become so distracted, busy trying to record these memorable events, that we’re actually missing out. Ironically, whilst making sure an imagined ‘future self’ has access to a tinny, shaky-cam approximation of what once occurred, we’re actually divorcing ourselves (our ‘current self’) from the moment, and any consequential sensory or emotional attachment.

The question for anyone who takes an interest in human experience is this: how might an individual find a way of living in the moment whilst also fulfilling the need a personal recording device appears to answer? We speculate this need goes beyond a social desire to share; it’s also to assuage a fear of forgetting – a concern that without the right prompts one cannot trust oneself to recall having been in such a place, and time, even when it seems so important.

Percolating Ideas

A few interesting things have come up recently – pub discussions, new applications of technology and ideas from literature, which have fuelled our development of what we’re calling the ‘Anti-Camera’.

Proust’s Madelines

In Swann’s Way, the first volume of Proust’s epic novel In Search of Lost Time, the narrator describes the involuntary memory triggered upon tasting a madeline dipped in tea. He recalls having tasted the same thing in his youth, and this recurrence – like a wormhole through space-time – takes him back to that moment and other memories that followed.

The link between memory and smell/ taste is well researched; the olfactory bulb is part of the limbic system – an area of the brain closely associated with memory. We really liked the idea that a time could be ‘stamped’ in some way by a strong taste or olfactory sensation – and then recalled later by re-experiencing the same flavour.

Black Mirror: The Entire History Of You

A ‘solution’ of sorts was modelled in the third episode of Black Mirror, written by Jesse Armstrong and directed by Brian Welsh. A theoretical passive recording device would allow us live out salient moments without distraction, but still have them recorded to remember – or more correctly re-experience (The distinction between the two is quite interesting). The program takes a cynical view of such a technology, and how it might have a degrading effect on our lives, but it prompts an interesting discussion on the role of technology in aiding or subverting memory.

Olly/ Foundry @ Mint Digital

The good guys from last year’s Mint Foundry did some nice prototyping to figure out how to interface smell-delivery systems via Arduino. They demonstrated how it was possible to release smell on demand digitally, and their experiments eventually led to Olly.

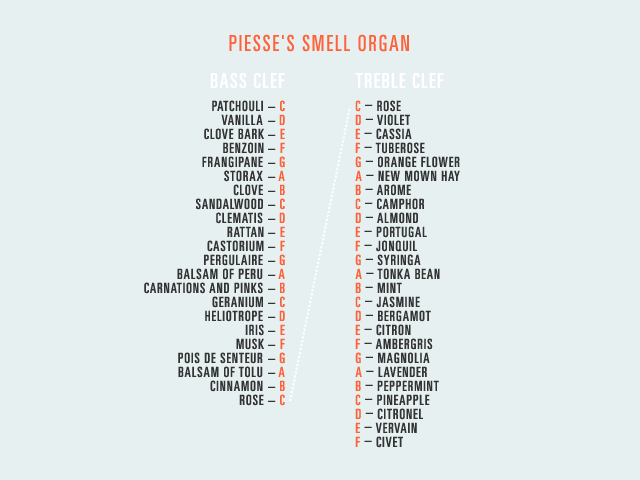

Piesse’s “Smell Organ”

Annoyingly, I can’t remember the source (a Bruce Sterling tweet?), but there’s an amazing entry in The Dead Media Project about a pipe organ designed by a French chemist in the 1920’s to “translate music into corresponding odors” – essentially an instrument that would play olfactory translations of classical pieces. The most profound aspect of this idea was the careful selection of which smell would represent each note, and how the treble and bass clef would complement each other. There’s a fantastically literal parallel between music and perfume’s high/ top notes and low/ end notes:

Look Outside, Y’all

So says creator Tom Scott:

“@LookOutsideYall is a Twitter bot that checks Instagram once a day, a few minutes before sunset. If it sees that a good proportion of photos around London are tagged or described with sunset, then it’ll tell the internet that it, collectively, should go outside and take a look at it.”

All the news surrounding Instagram’s popularity and assumed value illustrates how preoccupied we are with recording moments in time. Tom’s project further demonstrates how often people are using their camera phones to capture beautiful, fleeting moments. The apex of any crepuscular event is short, but this is when we’re bowing our heads and fiddling with technology – choosing filters, finding signal, signing in, writing hashtags…

The subtle difference in Instagram however is it’s quasi digi-folk artistry – we use it creatively to express a sense of something to others, not as a way to jog our own memories.

The Descriptive Camera

We got quite excited when Matt Richardson’s Descriptive Camera began to hit the feeds. Here was a device that took the photo out of the camera – and it was brilliant. Matt’s description of the purpose for such speculative tech was as follows:

“As we amass an incredible amount of photos, it becomes increasingly difficult to manage our collections. Imagine if descriptive metadata about each photo could be appended to the image on the fly.”

This was a smart idea, and such an application of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk was inspired, but we thought the real beauty here was in providing all the qualities of a camera without the photo.

Make-Your-Own-Perfume services

It turns out there is an enormous mass-customisation market in personalised perfumes, which has made the science of fragrance composition accessible to consumers – and more transparent for us.

The Anti-Camera

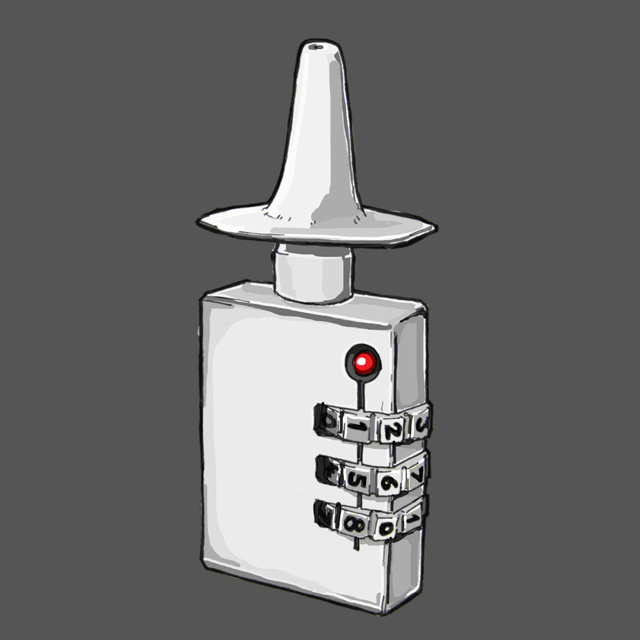

The idea is this: the Anti-Camera doesn’t record anything, nor does it output any simulacra. Rather, it coerces our mind into recollecting the essence of a moment – something less tangible than an image can capture. The device is designed to tag a moment in time with a unique olfactory identifier code – a bespoke smell. Then, when wishing to recall the moment at their leisure, the user of such a device could recreate the unique smell.

Olfactory Composition

Initially, we thought it would be satisfactory to use a binary, 8-bit smell generator – i.e. 8 smells, either on or off, allowing 256 combinations from 00000001 to 11111111. However, this method would provide very little distinction between neighbouring, or otherwise similar smells.

Instead, we’ve been looking at creating olfactory identifier codes composed of three parts – a top note, a middle note and an end note. For example, combining three ‘magazines’, each containing eight note ‘cells’, would allow for 512 permutations. Modern perfumers have access to several thousand unique ingredients, so many further magazines could be used in different combinations, allowing practically endless permutations.

Form

At first, we wondered if the anti-camera should still skeuomorphically conform to a camera-esque typology (weight, size, right-of-centre button etc.). There were the usual arguments for and against…

… at this stage we’re leaning towards making something completely different. Here’s an early concept sketch:

Next Steps – Prototyping

It’s early days and we’ve got a lot of theory floating around. Moving forwards we’re planning to get a few proof-of-concept models under way, testing to see if the idea will withstand some critical interrogation.