Sensory Augmentation: Vision (pt. 1)

Sam Hill

30th August 2011

Blinkered

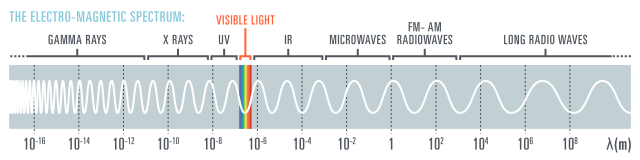

The above diagram illustrates the full breadth of the electro-magnetic spectrum, from tiny sub-atomic gamma rays to radio waves larger than the earth (there are in fact, no theoretical limits in either direction). That thin technicoloured band of ‘visible light’ is the only bit our human eyes can detect. That’s it. Our visual faculties are blinkered to a 400-800 Terahertz range. And from within these parameters we try as best we can to make sense of our universe.

There is no escaping the fact that our experience of the environment is limited by the capacity of our senses. Our visual, aural, haptic and olfactory systems respond to stimuli – they read “clues” from our environment – from which we piece together a limited interpretation of reality.

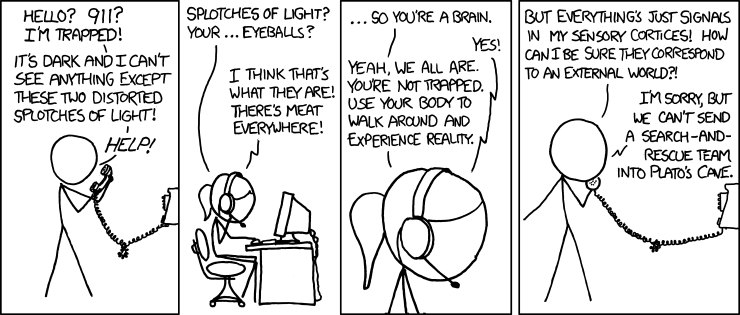

So says xkcd:

This limited faculty has suited us fine, to date. But it follows that if we can augment our senses, we can also increase our capacity for experience.

Seeing beyond visible light

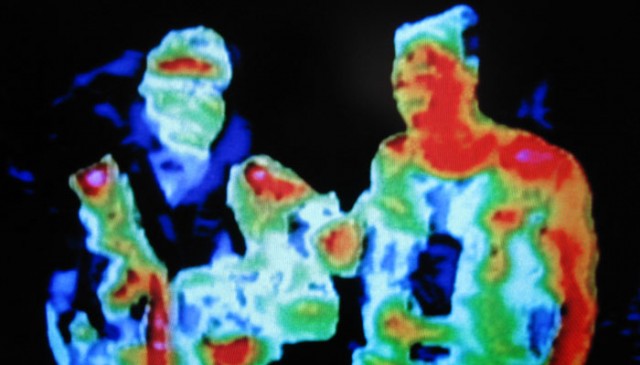

Devices do already exist that can process EM sources into data that we can interpret: X-ray machines, UV filters, cargo scanners, black-lights, radar, MRI scanners, night-vision goggles and satellites all exploit EM waves of various frequencies to extend our perceptions. As do infrared thermographic cameras, as made popular by the Predator (1987).

What are the implications of para-light vision?

Let’s for one second ignore a canonical issue with the Predator films – that the aliens sort of had natural thermal vision anyway and pretend they can normally see visible light. Let’s also ignore the technical fact that the shots weren’t captured with a thermal imaging camera (they don’t work well in the rainforest, apparently). Let’s assume instead that we have a boxfresh false-colour infra-red system integrated into a headset, and that human eyes could use it. How effective would it be?

First of all, we’re talking about optical apparatus, something worn passively rather than a tool used actively (such as a camera, or scanner). The design needs special consideration. An x-ray scanner at an airport is an unwieldy piece of kit, but it can feed data to a monitor all day without diminishing the sensory capacity of the airport security staff that use it. They can always look away. If predator vision goggles were in use today, they would be burdened with a problem similar to military-grade “night-vision” goggles.

Predator Vision is not a true sensory augmentation in that it does not *actually* show radiating heat. Instead it piggy-backs off the visible-light capability of the eye and codifies heat emissions into an analogical form that can be made sense of: i.e. false-colour. In order to do so, a whole new competing layer of data must replace or lie above – and so interfere with – any visible light that is already being received.

Predator Vision in the home

For example, let’s task The Predator with a household chore. He must wash the dishes. The predator doesn’t have a dishwasher. There are two perceivable hazards: the first is scolding oneself with hot water, which Predator Vision can detect; the second is cutting oneself on a submerged kitchen knife, which only visible light can identify (assuming the washing up liquid isn’t too bubbly). Infra-red radiation cannot permeate the water’s surface. What is The Predator to do?

He would probably have to toggle between the two – viewing in IR first to get the correct water temperature, then visible light afterwards. But a user-experience specialist will tell you this is not ideal – switching between modes is jarring and inconvenient, and it also means the secondary sense can’t be used in anticipation. A careless Predator in the kitchen might still accidentally burn himself on a forgotten electric cooker ring. The two ideally want to be used in tandem.

What’s the solution?

It’s a tricky one. How can we augment our perception if any attempt to do so is going to compromise what we already have? Trying to relay too much information optically is going to cause too much noise to be decipherable (remember our ultimate goal is to have as much of the EM spectrum perceptible as possible, not just IR). This old TNG clip illustrates the point quite nicely:

Here Geordi claims that he has learned how to “select what I want and disregard the rest”. Given the masking effect of layering information, the ability to “learn” such a skill seems improbable. It seems as likely as, say, someone learning to read all the values from dozens of spreadsheets, overprinted onto one page. However, the idea of ‘selectivity’ is otherwise believable – we already have such a capacity of sorts. Our eyes are not like scanners, nor cameras. We don’t give equal worth to everything we see at once, but rather the brain focuses on what is likely to be salient. This is demonstrable with the following test:

It’s also worth noting the unconscious efforts our optical system makes to enhance visibility. Our irides contract or expand to control the amount of light entering our eyes, and the rod-cells in the retina adjust in low-light conditions to give us that certain degree of night-vision we notice after several minutes in the dark. The lenses of our eyes can be compressed to change their focal length. In other words the eye can calibrate itself autonomously, to an extent, and this should be remembered from a biomimetric perspective.

Option one:

The most immediate answer to para-light vision is a wearable, relatively non-invasive piece of headgear that works through the eye. In order to compensate for an all visible-light output, the headgear would need to work intelligently, with a sympathetic on-board computer. The full scope of this might be difficult to foresee here. Different frequencies of EM radiation might need to be weighted for likely importance – perhaps by default visible light would occupy 60% of total sight, 10% each for IR and UV, and 20% for the remaining wavelengths. A smart system could help make pre-emptive decisions for the viewer on what they might want to know, e.g. maybe only objects radiating heat above 55ºC would be shown to give off infra-red light (our temperature pain threshold). Or maybe different frequencies take over if primary sight is failing. Eye tracking could be used to help the intelligent system make sense of what the viewer is trying to see and respond accordingly. This might fix the toggling-between-modes issue raised earlier.

It’s interesting to wonder what it would mean to perceive radio-bands such as for wi-fi or RFID – obviously, it would be fascinating to observe them in effect, but might their pervasion be over-bearing? Perhaps the data could be presented non-literally, but processed and shown graphically/diagrammatically?

Option Two:

The second, more outlandish option is a cybernetic one. Imagine if new perceptions could be ported directly to the brain, without relying on pre-formed synaptic systems. Completely new senses. Perhaps existing parts of the brain could accept these ported senses. The phenomenon of synesthesia comes to mind, where stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. Is it possible that in a similar vein the visual cortex could read non-optic information, and would that help us to see several types of information simultaneously but allow us to selectively choose which parts to focus on? If such a segue weren’t possible, would a neural implant bridge the gap?

In Summary

I’ve intentionally only discussed the EM scale here, but of course there are many other forms of data that can be visualised. There might be potential for augmenting vision with sonar, for example, or miscroscopy. Human-centric metadata deserves a whole post in it’s own right.

It’s difficult to predict how the potential for sensory augmentation will change, but whatever opportunities pioneering science unlocks can be followed up with tactical design consideration to make sure applications are appropriately effective and adoptable. It’s an exciting prospect to think that we may be on the threshold of viewing the world in new, never-before seen ways – and with this new vision there will be, inevitably, new points of inspiration and new ways of thinking.