The Logic in Paul’s Gamble

Sam Hill

21st March 2012

Yesterday we released the third instalment of Paul’s Gamble. The web series is to be released in 12 weekly parts and explores the contentious nature of gambling.

(warning – spoilers below)

The General Idea

Paul McNicholl is a mate of PAN and our eponymous hero. He recently decided to quit smoking though not for the first time – he’s tried existing products and services to help, but hasn’t had that much success. Before starting this project Paul was typically smoking the equivalent of one pack/ 20 cigarettes a day, which works out as about seven or eight quid every 24 hours/ £250 a month. It’s this cost (being far more tangible than the health issues) that has really started to get to him.

When Paul said he was thinking of gambling his money rather than spending it on cigarettes, we got really excited and suggested the format. Paul liked the idea, probably because our involvement would give him a bit more motivation. Between us we decided to start during the difficult “third week” – when the cravings are supposed to be strongest.

Attitudes to Gambling

‘Gambling’ is a pretty divisive concept – frowned upon about as much as it’s practised. But despite criticisms of the gambling industry, the over-all idea of risk-taking is a critical part of life – both in daily decisions and the greater biological scheme of things.

As a pastime it’s about 40,000 years old and a textbook ‘meme’ in Richard Dawkins’ original sense – a concept that continues to abide even if it doesn’t necessarily benefit those that prescribe to it.

The reasons for cynicism towards gambling or ‘gaming’ can be unwrapped as follows:

- If the odds are always stacked against the player (“the house always wins”) then choosing to gamble is illogical. A gambler could easily be accused of poor judgement.

- Gambling provides the chance for an individual to profit purely through luck, and requires neither skill nor labour. In doing so it subverts our model of society – where the individual and the whole have a reciprocal relationship. It’s therefore often unpopular with the state, or ruling class and is portrayed (perhaps fairly) as corrupting – encouraging both greed and slothfulness. To be fair, this condemnation seems to go out of the window when it comes to state lotteries.

- The psychological (if not financial) rewards of gambling can lead to addictive behaviour. Ludomania (problem gambling) is sometime compared with substance abuse disorders.

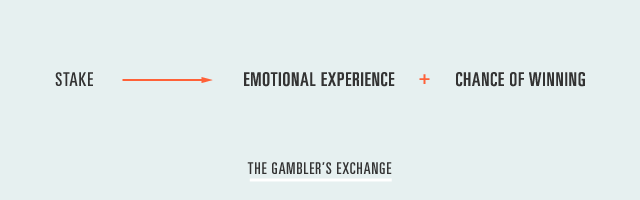

The Point of this Experiment

The rewards of taking a risk go beyond the potential prize. Win or lose, there is a guaranteed return on investment in the form of a rich experience. The learning aspect might sometimes be a tad weak-sauce (the roulette wheel finished on red… so therefore we know that sometimes the wheel will finish on red) but the emotional experience can be very strong – thrill, apprehension, shame, glory . The intensity of these feelings is proportional to the stake invested and the potential prize – not as fixed amounts, but as a fraction of the individuals resources (a millionaire and someone living below the poverty line would not feel the same about a £1000 game of Blackjack). The emotional journey is an example of a trajectory we previously described as Intervention Type #1 in a previous post, i.e. something with a beginning, middle and end – the decision, the anticipation and the result.

We believe that it doesn’t particularly matter experientially whether the individual wins or loses, so long as the outcome has an intensity. Paul is gambling instead of smoking – will his life be more enriched as a consequence? I don’t mean because of the health benefits either – but because of the relative intensity of emotion.

This is the moment when Paul realises that 1) His team have won the match, and 2) He has just won £200. Look at his face! That is a face expressing raw, powerful emotion. I envy Paul enormously for that moment in time. He has the fortune now of replaying this second in his mind (and on film) for the rest of his life.

In Summary

We got Paul trying a different activity in each episode because the richness of experience is dependent on novelty; returns diminish over time. If we were to organise ten days of roulette then by the end he would be no better off than he was smoking (again, health effects to one side).

Risk assessment is a naturally evolved process. All living things need to carefully manage their energy resources and so end up developing heuristic or instinctive systems to survive. Yes it’s true that if any creature adopts a behaviour that invests too much into risks with poor odds or low yields then it will perish. However, at the same time a risk-averse creature will fail to flourish – especially in a competitive environment. By stripping the extremes from the gene pool natural selection moderates risk-taking to an apt degree.

Seeing as risks are essentially ‘commitments to actions where the outcomes are uncertain’, and that ‘certainty’ is a fairly abstract idea, we can gather that risk-taking is also practically ubiquitous, even if the risks are marginal (quantum, even).

We’re not going to directly condone gambling – elements of it are cynical and exploitative. But when considered primarily as a form of entertainment, rather than an economic strategy, then it makes a lot more sense. If the stake is always considered to be a ticket – a variable price for an experience that scales to whatever the participant can afford – then there’s no reason why in the long-term any loss should be resented, or regretted.