Sensory Deprivation Experience

Sam Hill

7th February 2012

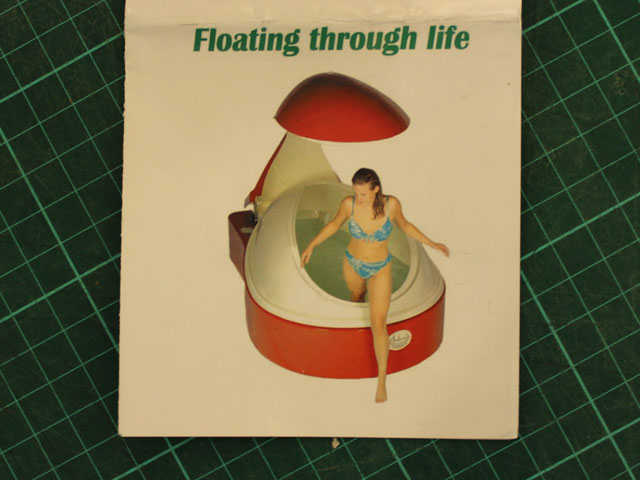

Last week I made use of my first ever Groupon purchase – a one hour session in a floatation tank.

My understanding was that such experiences centre around sensory deprivation – no sight, no sound, no smell… the body is kept buoyant by a salt solution, heated to human body temperature, which nullifies the effects of gravity and creates a sensation of weightlessness.

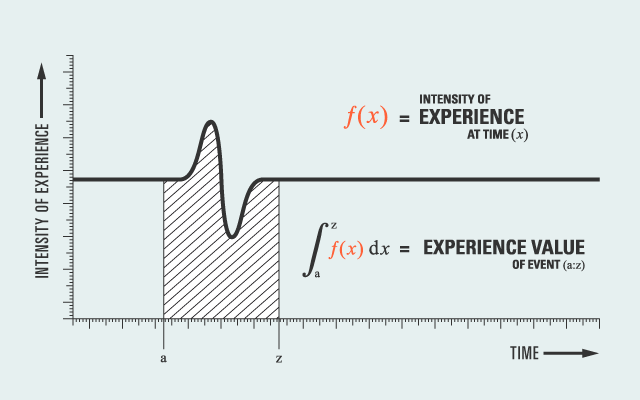

The value of sensory deprivation is very interesting from a theoretical perspective. After all, if the theories we’re exploring suggest rich experiences are ultimately dependent on sensory input, and implicitly improved by greater intensity of sensation, then what would it mean to completely deny oneself of sensation as a route to experience? Can experiences be internalised? Would attempting to do so validate or invalidate our argument? Promotional literature for floatation therapy seems to suggest it is an enlightening, zen-like experience – placing the individual in a quasi-meditative state. It raises some fairly difficult issues regarding the experiential benefit of meditative thought. Obviously, this one-off event was always going to be novel in any case and would so be an enriching experience regardless of how little sensation was technically delivered – but are there long term experiential benefits to dedicating time to meditative thought (when time is such a precious commodity)?

Using the Floatation Tank

As it happened, the experience wasn’t a completely perfect case for analysis. Though it was more than adequate for it’s intended uses (relaxation, physiotherapy, catharsis) the tank did not truly deny all sensation – a tiny amount of light leaked in through the fixings, nearby traffic was just audible through the ear plugs, the water was slightly warmer than body temperature. Though this seems like nit-picking, there is a world of difference between fractional sensation and none whatsoever. In addition, this was the first time I’d done anything like floatation therapy so, as the instructor expected, it took (me) my mind quite a while to adjust to the change – I felt like my brain was urgently firing off a jumble of thoughts for the first quarter of an hour to compensate for the strange environment.

Having said all that I did, I think, get into a different mindset about half way through the hour. I felt calm, adjusted and numb. I lost track of time. The tension melted from postural muscles I didn’t realise I was knotting. A few joints had popped and snapped in very satisfying ways. My consciousness had exhausted it’s analysis of the context and was looking inwards.

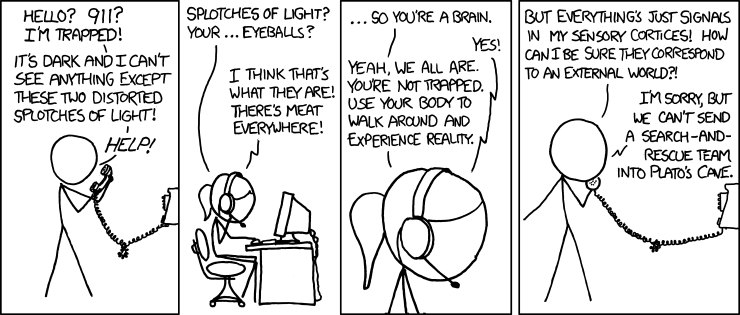

I’ll be very honest with you. I actually felt incredibly contented. Not happy, necessarily, but just very comfortable with where I was. Doing nothing. The immediate future did not matter, nor did the world outside the water tank. Then inevitably the discussion I’d been having with Ben a few weeks ago percolated up through my subconscious. I remember we discussed what it means to limit oneself from interacting with the surrounding world. I realised I was (with no melodrama implied) closer to “death” than I’d ever been. That’s not to say I was in any real way close to dying, of course, but I was removed from existence as much as a rational and lucid mind could be – I had severed any real link with (weasel word) ‘reality’ and was inhabiting an abstract non-context.

I then did a very stupid thing and rubbed my eyes. My fingers were covered in the magnesium sulphate solution and it caused a fairly nasty stinging sensation I couldn’t escape from. It probably wouldn’t have been that bad normally but this was the only thing I could feel, which meant it was the only thing I could think about. I snapped out of any kind of state that I might have been in and was jerked back into reality. It was difficult from that point on to return to any kind of meditative or theta-level state.

The idea that pain can bring an individual from a state of detachment to feeling alive synchronises well with a ‘pure’ experiential viewpoint, which suggests that all sensations (good or bad) have a richness of value. However I was startled by a more sinister parallel – using pain to feel connected and alive is sometimes cited as one psychological explanation for self harm. This should be acknowledged, I feel, but it should also be noted that emotional detachment and sensory detachment are two very different fish kettles.

Conclusion

Research into sensory deprivation appears to show there are cognitive benefits associated with occasional use but as with anything, prolonging sessions provides diminishing returns, eventually becoming counter-productive.

Returning to the difficult question ‘is there an experiential value in meditation?’, the issue is clearly more than a little complex. Unfortunately I’ve not much personal experience to draw from, other than this isolated event.

There are many interpretations of what meditation means and what purpose it serves. A cynic might claim it is mostly a waste of time – certainly an individual engaged in meditation is ‘doing’ nothing, so how can it be seen to be productive?

Is this fair? We might say one of the many interpretations is that meditation is a process conducive for focused thought. If this were so, then perhaps yes, it could be perceived as experientially rich, because concentrated enquiry can help us to rationalise, conclude and review – to make knowledge from data.

Applications

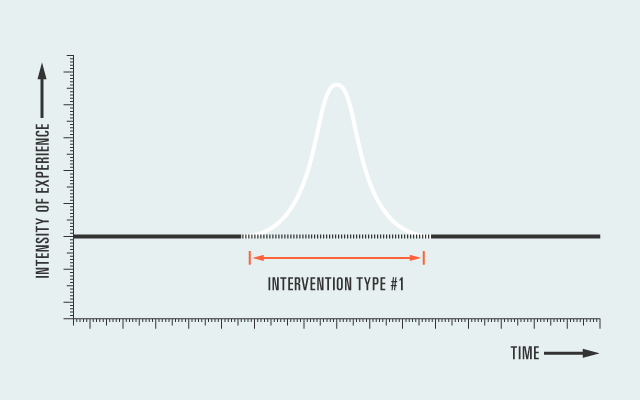

Knowledge is a critical element of experience value. This implies that an appropriate meditative session should be undertaken soon after any experientially rich happening in order to help exploit the maximum experiential potential from it. If this were the case, how would that effect the closure of experience-services, such as the credits to a film, or the returning flight from a holiday?

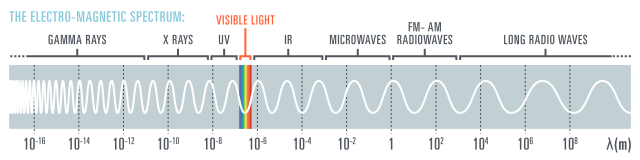

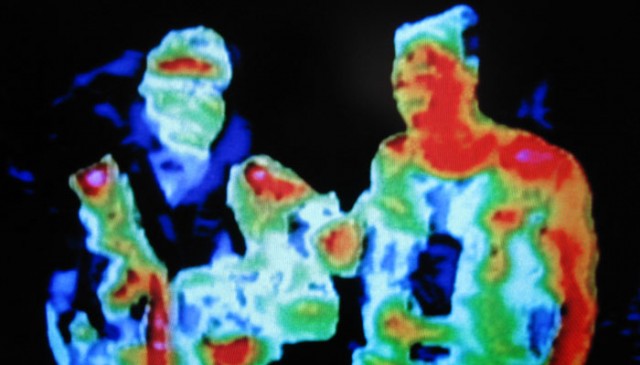

Sensory deprivation can also be very useful when used in combination with any tele- or pseudo-sensory application. That is to say, if there is a desire to have an individual be completely immersed in a non-local experience then they should be sensationally divorced from their immediate context. Some culturally close-to-hand examples include the ubiquitous goo baths of Minority Report, The Matrix, BSG and Avatar.

goo baths – from various sci-fi sources

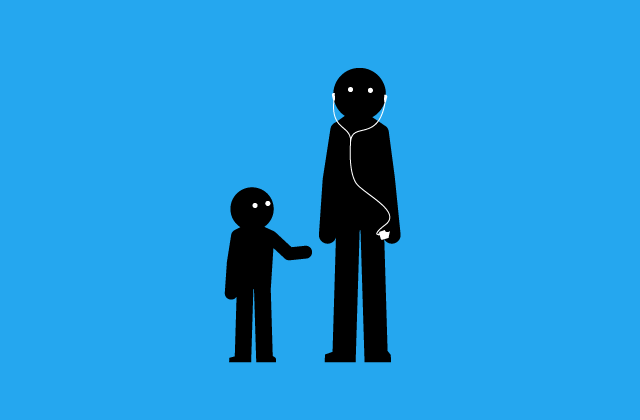

Another more tangible example is Auger & Loizeau’s Isophone – paired communication devices that ensures the individuals using them have each other’s undivided attention.