Experience, Identity and Ideology

Sam Hill

29th June 2012

There is an integral relationship between personal experience, identity and ideology. This relationship was touched upon briefly by political philosopher Robert Nozick in the “Experience Machine” thought experiment, which he published as part of his seminal work Anarchy, State and Utopia in the mid-seventies. The relationship was also discussed in more detail about ten years ago by Harvard business academics James Gilmore and Joseph Pine in The Experience Economy.

What makes these two points of view particularly interesting is that they both attempt to place the value of experience within a greater context – spiritually, economically and philosophically. Nozick treats personal experiences, personal identity and the application of personal belief as parallel value sets (intrinsic multism), but does not necessarily assign them relative worth (only stating that experience is not the be-all and end-all). Gilmore and Pine however describe experience and transformation as progressive stepping stones towards the pursuit of something altogether more spiritual – a monistic eternality, religious imperative or transcendent value (did I mention theirs was a business book?).

Both of these arguments go some way to marginalising the value of experience. Nozick is more directly attacking hedonic utilitarianism than what might be called ‘experientialism’, but his arguments still appear (certainly at face value) to be valid by proxy. Gilmore and Pine believe experiences to be important (that is the main purpose of the book) but ultimately only as a means to an end. They don’t consider experiences to be intrinsically valuable.

Nozick’s Experience Machine

Here’s a heavily abridged version of Nozick’s Experience Machine thought experiment. I would highly recommend reading the whole chapter (… and the whole book) but this is all that is immediately relevant – Nozick is discussing the implications of a more-or-less permanent existence within a simulated reality:

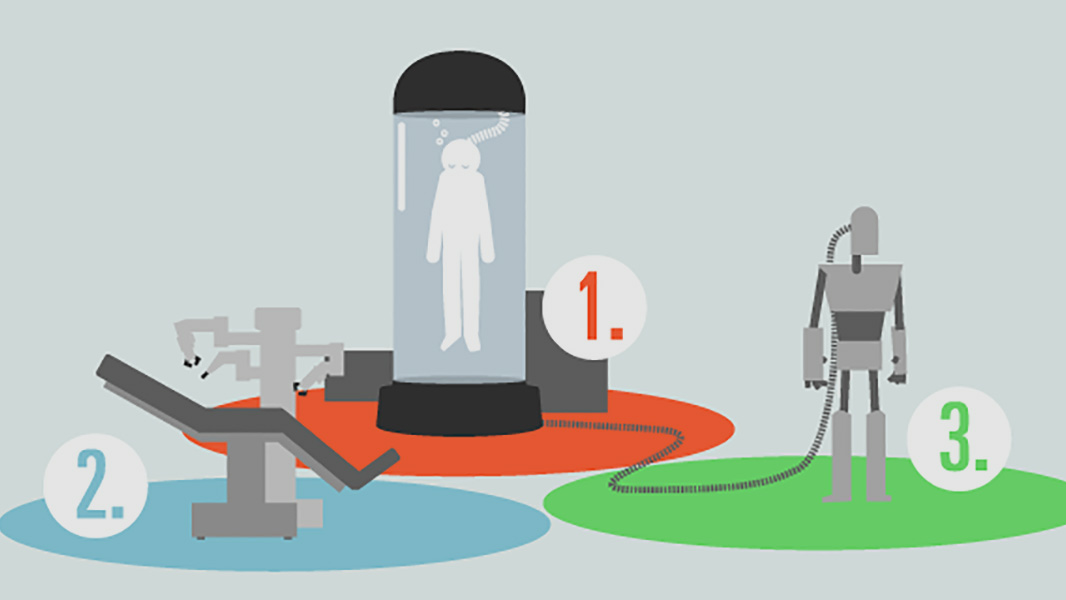

“Suppose there were an experience machine [1] that would give you any experience you desired… Would you plug in? What else can matter to us, other than how our lives feel from the inside?… First, we want to do certain things, and not just have the experience of doing them. In the case of certain experiences, it is only because first we want to do the actions that we want the experiences of doing them or thinking we’ve done them. (But why do we want to do the activities rather than merely to experience them?) A second reason for not plugging in is that we want to be a certain way, to be a certain sort of person. Someone floating in a tank is an indeterminate blob. There is no answer to the question of what a person is like who has long been in the tank. Is he courageous, kind, intelligent, witty, loving? It’s not merely that it’s difficult to tell; there’s no way he is. Plugging into the machine is a kind of suicide… But should it be surprising that what we are is important to us? Why should we be concerned only with how our time is filled, but not with what we are?

…We learn that something matters to us in addition to experience by imagining an experience machine and then realizing that we would not use it. We can continue to imagine a sequence of machines each designed to fill lacks suggested for the earlier machines. For example, since the experience machine doesn’t meet our desire to be a certain way, imagine a transformation machine [2] which transforms us into whatever sort of person we’d like to be (compatible with our staying us). Surely one would not use the transformation machine to become as one would wish, and there-upon plug into the experience machine! So something matters in addition to one’s experiences and what one is like… Is it that we want to make a difference in the world? Consider then the result machine [3], which produces in the world any result you would produce and injects your vector input into any joint activity… What is most disturbing about [these machines] is their living of our lives for us… Perhaps what we desire is to live (an active verb) ourselves, in contact with reality. (And this, machines cannot do for us.)”

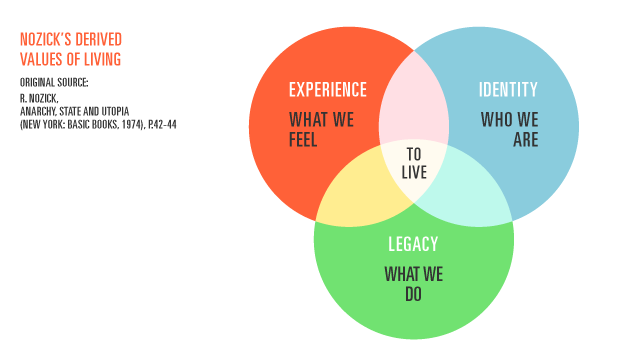

From his exploration we can summarise the values that Nozick’s thought-experiment reveals to be apparently important to us:

To live, he infers, is the combined product of many things – reducible to a number of core values. Nozick hints there may be more then he has mentioned here.

Gilmore and Pine’s Transcendence of Experiences to Transformations

Gilmore and Pine write:

“… Remember, in the nascent Transformation Economy, the customer is the product and the transformation is an aid in changing the traits of the individual who buys it… Certainly, competitors can duplicate specific diagnoses, experiences, and follow-through devices, but no one can commoditize the most important aspect of a transformation: the unique relationship formed between the guided and the guide. It is the tie that binds.

An offering of a higher order can supersede lower-echelon relationships. But the only offering that can displace a transformation is yet another transformation – one aimed at another dimension of self, or at the same dimension but from a different world-view. By world-view, we mean a particular way – often religious or philosophical – of interpreting one’s own existence. In the years ahead, we think that companies and their customers will increasingly acknowledge rival world-views – ideologies, if you will – as the legitimate domain of business and as differentiators of competing offerings… Consider the fundamental nature of each offering:

- Commodities are only raw materials for the goods they make

- Goods are only physical embodiments of the services they deliver

- Services are only intangible operations for the experiences they stage

- Experiences are only memorable events for the transformations they guide

Then reflect on our personal belief that:

- Transformations are only temporal states for the eternalities they glorify.

All economic offerings do more than effect an exchange of value in the present; they also, implicitly or explicitly, promote a certain world-view. In the full-fledged Transformation Economy, we believe buyers will purchase transformations according to the set of eternal principles the seller seeks to embrace – what together they believe will last.”

Now, when we compare Nozick’s derived values with Gilmore and Pine’s Progression of Economic Value we can see (assuming of course that one can agree firstly that ‘transformations’ equate to a matter of identity and secondly that any legacy we set out to achieve aligns with our life stance) the same three values are presented, but this time in a hierarchy based upon the economic principal of mass customisation. This can be shown as such:

Criticism of these approaches

Nozick, Gilmore and Pine are prolific thinkers, and I massively respect their work. For the most part these are both compelling theories (and it’s interesting to observe the parallels) but in each case I feel their ideas should be scrutinized further – mostly Nozick, who’s hypothetical experiment – brilliant as it is – was built seemingly tangentially on the way to another argument.

Nozick states: “We learn that something matters to us in addition to experience by imagining an experience machine and then realizing that we would not use it”. This seems unduly dismissive. To begin with, people already do embrace fore-runners of the experience machine – the ever-growing computer game market already provides us the capacity for continuous, uninterrupted synthetic experience. Condonable or not, people have dedicated years to their MMO accounts, RTS ladders and Xbox Live scores and at the extreme this has had the predicted detrimental effects to their real-world development and activity.

One might argue then that Nozick is really saying “…we should not use it”. Well, in this case, we’d need to rule out the possibility our reservations are irrational, or poorly founded. Perhaps, for example, the association we have with the word “machine” is too strong; we can’t fathom the idea of a truly authentic digital experience – even with all the caveats in the world – if the uncanny valley has left us irreparably prejudiced.

There seems to be a disparity, for example, between what constitutes an ‘authentic’ orchestrated experience, depending on whether it is positive or negative. An individual recounting the value of a positive digital experience might be scoffed at for buying into something synthetic, but would anyone doubt the sincerity of any trauma derived from an artificial nightmare?

An important clarification should be made of how the ‘experience machine’ really functions. Does any free will still exist within the system? Would free will matter if the system still compensated accordingly to produce the same outcome? Is the individual obliged (unknowingly) into an unwavering destiny – as if tied to the front of a train – or can they exercise even a modicum of choice – like an oarsman travelling along a river? The latter still allows an individual to be something other than an “indeterminate blob”. Perhaps identity is found in choice, and the broader the scope for choice, the better one’s identity is defined.

Who we are and what we do are very difficult things to untangle. In the same way that cinema uses frames to create the illusion of a moving image, consecutive experiences might create the illusion that there is a consistency in our identity. We’re so dependent on the contexts we find ourselves in when deciding what choices to make. But does identity exist in a vacuum? Are we really so immutable, or is this illusion a consequence of story-telling – the ubiquitous myth that we are like the characters we learn from in narratives – predictable, serialised and defined. Are we all that different from how everyone else would be, if obliged to wear our shoes?

The nature of ‘transformation’ – an effort to change one’s identity – further compounds this abstraction. How can someone will themselves to be different? How can they will themselves in the future to make a different decision to one they’d currently make? What voluntary procedure helps an individual do this? As Nozick says: “imagine a transformation machine which transforms us into whatever sort of person we’d like to be (compatible with our staying us)”. The idea is nonsensical; the caveat is too open-ended. If identity really is a constant, then to be a different person – by definition – would stop one remaining oneself. The best we can hope for is to change our context.

This is what really happens when individuals use the closest equivalents to transformation machines – they visit therapists to re-frame the perceived consequences of their behaviour; they pay plastic surgeons to make cosmetic differences to their appearances; they take drugs to alter their perceptions and they enter lotteries to change their wealth.

Defining Transformations

It’s useful to understand personal transformation by thinking of the industries that deliver changes to ourselves. Many of these industries are more typically associated with bringing traits of inadequacy up to a median standard, but some are concerned with the improvement of oneself above and beyond what is considered ‘normal’.

We have, for example:

- Medicine, dentistry and healthcare

- Personal (physical) trainers and gymnasiums

- Mental health care – psychiatry, therapy

- Self-help literature, courses and life coaches

- NLP and hypnotherapy

- Skills training and further education – tutors, teachers, mentors

- Dietary specialists

- Libraries, wikis and learning/ information resources

- Beauticians – plastic surgeons, cosmetologists and fashionistas

- Bionics, mobility devices and sensory augmentation (including eye wear and hearing aids)

(it’s important to note that these are self-initiated transformations. Not included here are the coercive transformations applied to individuals by others, groups, states or organisations – such as advertisement and compulsory education)

When compared with what are considered to be established and accepted experiential industries we notice something quite interesting. For example consider:

- Performing arts – cinema, theatre, dance, music

- Sport – played and spectated

- Literature – poetry and prose

- Fine arts

- Events and installations

- The gaming industries

- Leisure and tourism

- Cuisine

What is the difference between these two groups of industry? Moreover, what’s the difference between a diet and a feast? What’s the difference between an hour on a treadmill and an hour at a theme park?

The distinction is not that one is emotionally positive whilst the other is negative, because that is not necessarily important for experiential richness. The distinction is instead that one is stimulating and novel, whist the other is more commonly drudgerous and repetitive. The very purpose of the transformative industries is to assist people in making changes about themselves, and the reason people have not already made these changes independently (and thus demand the ‘service’) is commonly a matter of motivation.

There are a couple of points to conclude with here. First of all, how can a transformation be considered a transcendence of an experience, as Gilmore and Pine describe? How can a calorie controlled diet be the transcendence of the food consumption experience? Secondly, what happens when Nozick’s derived values conflict – i.e. between what we want to do and what we want to be? I might want to be as healthy as an athlete, but I still want to experience sedentary pursuits and eat chocolate cake.